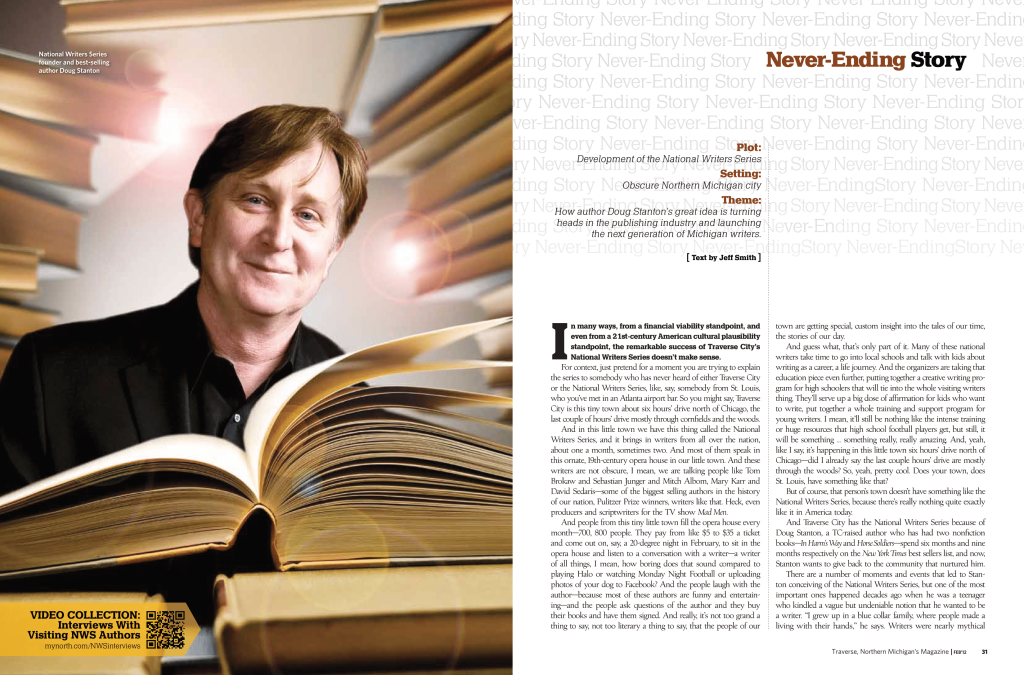

PLOT: Development of the National Writers Series

SETTING: Obscure Northern Michigan City

THEME: How Author Doug Stanton’s great idea is turning heads in the publishing industry and launching the next generation of Michigan writers

In many ways, from a financial viability standpoint, and even from a 21st-century American cultural plausibility standpoint, the remarkable success of Traverse City’s National Writers Series doesn’t make sense.

For context, just pretend for a moment you are trying to explain the series to somebody who has never heard of either Traverse City or the National Writers Series, like, say, somebody from St. Louis, who you’ve met in an Atlanta airport bar. So you might say, Traverse City is this tiny town about six hours’ drive north of Chicago, the last couple of hours’ drive mostly through cornfields and the woods.

And in this little town we have this thing called the National Writers Series, and it brings in writers from all over the nation, about one a month, sometimes two. And most of them speak in this ornate, 19th-century opera house in our little town. And these writers are not obscure, I mean, we are talking people like Tom Brokaw and Sebastian Junger and Mitch Albom, Mary Karr and David Sedaris—some of the biggest selling authors in the history of our nation, Pulitzer Prize winners, writers like that. Heck, even producers and scriptwriters for the TV show Mad Men.

And people from this tiny little town fill the opera house every month—700, 800 people. They pay from like $5 to $35 a ticket and come out on, say, a 20-degree night in February, to sit in the opera house and listen to a conversation with a writer—a writer of all things, I mean, how boring does that sound compared to playing Halo or watching Monday Night Football or uploading photos of your dog to Facebook? And the people laugh with the author—because most of these authors are funny and entertaining—and the people ask questions of the author and they buy their books and have them signed. And really, it’s not too grand a thing to say, not too literary a thing to say, that the people of our town are getting special, custom insight into the tales of our time, the stories of our day.

And guess what, that’s only part of it. Many of these national writers take time to go into local schools and talk with kids about writing as a career, a life journey. And the organizers are taking that education piece even further, putting together a creative writing program for high schoolers that will tie into the whole visiting writers thing. They’ll serve up a big dose of affirmation for kids who want to write, put together a whole training and support program for young writers. I mean, it’ll still be nothing like the intense training or huge resources that high school football players get, but still, it will be something … something really, really amazing. And, yeah, like I say, it’s happening in this little town six hours’ drive north of Chicago—did I already say the last couple hours’ drive are mostly through the woods? So, yeah, pretty cool. Does your town, does St. Louis, have something like that?

But of course, that person’s town doesn’t have something like the National Writers Series, because there’s really nothing quite exactly like it in America today.

And Traverse City has the National Writers Series because of Doug Stanton, a TC-raised author who has had two nonfiction books—In Harm’s Way and Horse Soldiers—spend six months and nine months respectively on the New York Times bestsellers list, and now, Stanton wants to give back to the community that nurtured him.

There are a number of moments and events that led to Stanton conceiving of the National Writers Series, but one of the most important ones happened decades ago when he was a teenager who kindled a vague but undeniable notion that he wanted to be a writer. “I grew up in a blue-collar family, where people made a living with their hands,” he says. Writers were nearly mythical beings to him; their words appeared on the page, but since he’d never met one, they didn’t seem real. His dad, however, happened to have gone to grade school in Reed City, Michigan, with poet and novelist Jim Harrison. One day Stanton’s dad introduced the teen to Harrison, and the older author helped Stanton keep his writing desire alive and helped open the door to Esquire magazine, where he became a contributing editor at the age of 28.

Today, when teen writers call Stanton, he says, “I always call them back, because the only reason they have called me is that I’ve done these books, and the only reason I’ve done these books is that people like Jim Harrison paid attention to me when I was young. The only thing I ask of the kids who call is that when they are older, they return calls from students too.”

A similar notion—helping young people see writing as a real career—was behind Stanton’s desire to name the high school writing program The Front Street Writers Project and to find a space that is in fact right on Front Street, downtown Traverse City’s primary commercial thoroughfare. “It’s important to me to bring art and literature to Main Street and make it seem as easy or as normal as watching TV,” Stanton says. “By putting this on Front Street, with a big window facing the street, it says to everybody walking by that we value this as a community, that literature and writing is a part of the daily swirl of commerce that goes on downtown.”

The Front Street Writers Program will kick off this fall and would have to be considered a dream class for any aspiring young writer. “What I want it to do is replicate for high school students my two years in the writing program at the University of Iowa Writers Workshop,” Stanton says. The program will bring in a master’s in fine arts graduate student to teach the program each year and will augment with workshop time offered by nationally renowned writers who are stopping through for the speaking events. Helping run the program will be Michael Delp, author and recently retired writing instructor at Interlochen Arts Academy who has managed a similar MFA-based teaching program at Interlochen for years.

The Front Street Writers Program will be tied to Traverse City schools. During the week, students will be able to leave their schools and head downtown to study writing on Front Street, classwork for which they will receive credits. Of the two pillars the National Writers Series stands on—the writer events pillar and the high school workshop pillar—the high-profile writer event series has understandably overshadowed the educational piece of the program, but for Stanton, what the program does for kids “will be the program’s true legacy.”

It takes a little context to understand what it means to say there’s nothing quite like the National Writers Series in America today. There are similar programs, to be sure, where people gather to hear writers. But they most commonly are readings—writers stand on a stage and read their work with a little chitchat and background to glue it together. Or authors do traditional bookstore appearances, where they sit at a table, chat with customers and hope people buy their book. But the National Writers Series events are designed to be a conversation, a conversation in which the guest writer engages with both the interviewer on stage and the audience. The conversation touches on specific books and certainly the writer’s most recent book, which they are working hard to sell, but the conversation ranges more widely than that, so the audience learns about the individual writer’s process and life story, gets a taste of their humor and spirit. “I tell all the visiting writers, this isn’t English class,” Stanton says. The events are intended to be fun, entertaining, enlightening and informative.”

Just as Stanton’s personal experience lies at the heart of the Front Street Writers Program, his experience on book tours shaped the structure of the event piece. During his first big national book tour, the tour for In Harm’s Way, he hit 50 cities, and did a multitude of media interviews, many on national TV and radio shows, but also dozens with local print, radio and TV reporters. The tour, all arranged by the staff of his publisher, brought in thousands of people to his appearances and helped sell hundreds of thousands of books. Flash forward to his 2009 tour for Horse Soldiers, and Stanton found an entirely different world. The revolution in media combined with the recession meant “all the book review editors had been fired,” Stanton says.

Meanwhile publishers had begun to hold book tours to a tougher financial standard. “When your publisher calls the day after a bookstore event and says, ‘how many people showed up and how many books did you sell,’ and you say, ‘47 people and I sold 12 books,’ they aren’t going to invest in your book tour,” he says. And book tours—even for big-name authors—are not performing like they had previously, in part because local media coverage has essentially vanished, and it is so much more difficult to get the word out.

Take for example James Bradley’s experience on his book Flyboys. Bradley’s first book, Flags of our Fathers, was a gigantic bestseller about the raising of the flag at Iwo Jima. His follow-up book, Flyboys, was about the first President Bush’s harrowing experiences when shot down as a World War II flyer. “When Bradley went to Houston— Bush’s home state—for his book tour, he disovered that the media opportunities had largely evaporated,” Stanton says.

Publishers have replaced local media interviews with giant national media interviews, so on the Horse Soldiers tour, Stanton found himself speaking to, in one instance, 28 million people on a SiriusXM nationally broadcast satellite radio show. But he found the lack of human contact on the book tour very troubling. He kept asking himself, Where are the people?

Puzzled, he asked the people who squired him around cities on his book tour which author events were most successful. “They always said cookbook authors,” Stanton says. Why cookbook authors? Their events weren’t “readings,” they engaged the audience, they did something on stage—in this case, cooked—and they kept it light, entertaining.

When Stanton returned to Traverse City in May 2009, after his Horse Soldiers tour, he and his family held an event at the City Opera House that became the template for the National Writers Series. They filled the house, had food, and made it a conversation. A special guest on stage was one of the officers who was central to the Horse Soldiers story. “It was very fun, but also very emotional,” Stanton says. At the closing of that event, Stanton announced that “this was so much fun, we’re going to do this again.” And the National Writers Series was born. Stanton’s wife, Anne Stanton, and his friend Grant Parsons agreed to be co-founders. Today there’s even a small, hard-working staff, led by director Megan Raphael, but still no office.

To date, 42 writers have participated in the National Writers Series, including writers who agree to serve as the interviewers; events are typically at the City Opera House. And the writers have loved the event. They’ve been wowed by Traverse City’s hospitality and community embrace, and several have offered to return to serve as interviewers. Their publishers have taken note too. “My publisher called me and said, ‘You’ve been invited to this event and you WILL go. This is a plum,” says Paula McLain, author of The Paris Wife, a best-seller about Hemingway and his first wife’s life in Paris.

Sebastian Junger, the author of The Perfect Storm and more recently the journalist who collaborated on the Afghanistan war documentary film Restrepo, is a seasoned veteran of the book tour world. “It is a writer’s heaven,” he says of the National Writers Series event. “It is physically beautiful there, everyone is incredibly hospitable, and everyone seems to love books—the questions were really smart. For me, as an American writer, I really love finding a real community, a community of real people, that has a love of books. That is a wonderful combination.”

Jeff Smith is editor of Traverse, Northern Michigan’s Magazine.