Mermaids don’t exist. It’s a dull, disheartening truth that we all probably accepted in childhood, despite Disney’s best efforts. But whatif they did? Seated next to each other at a reading of Alison Swan’s Fresh Water anthology more than a decade ago, local authors Anne-Marie Oomen and Linda Nemec Foster found themselves asking this very question. Ten-odd years, countless emails, and one fateful weekend together in a motel on Lake Michigan later, their debut collaborative, The Lake Michigan Mermaid, is no longer just an exciting “what if”: as of this past March, it’s bound in hardcover.

Mermaids don’t exist. It’s a dull, disheartening truth that we all probably accepted in childhood, despite Disney’s best efforts. But whatif they did? Seated next to each other at a reading of Alison Swan’s Fresh Water anthology more than a decade ago, local authors Anne-Marie Oomen and Linda Nemec Foster found themselves asking this very question. Ten-odd years, countless emails, and one fateful weekend together in a motel on Lake Michigan later, their debut collaborative, The Lake Michigan Mermaid, is no longer just an exciting “what if”: as of this past March, it’s bound in hardcover.

At the surface, the book tells the story of Lyk — Lykretia, a name from Oomen’s imagination, meaning “joy” — an only child living on the shores of Lake Michigan, and the connection she develops with the mermaid who shares her beach. But the story itself isn’t the first thing we notice; in fact, we don’t really discover the storyline until we’re three or four pages in. This is because the book is structured as an expertly interwoven series of poems. According to Oomen, the call-and-response structure of the book was something the two women sought from the start: “Driving home from Saugatuck that night, I called [Foster], and said, “I think we should do something with this mermaid idea. I think there’s something there.” The first thing Linda said to me was, “I want to be the mermaid!” My poems often have a narrative impulse; [Linda’s] are very lyric. I was almost from the beginning seeking some kind of very loose storyline. So right away, there were two voices, and we would be personas, not ourselves. We agreed quickly that we’d write very small, back-and-forth pieces month to month, from time to time, and we both agreed we’d keep it a secret.”

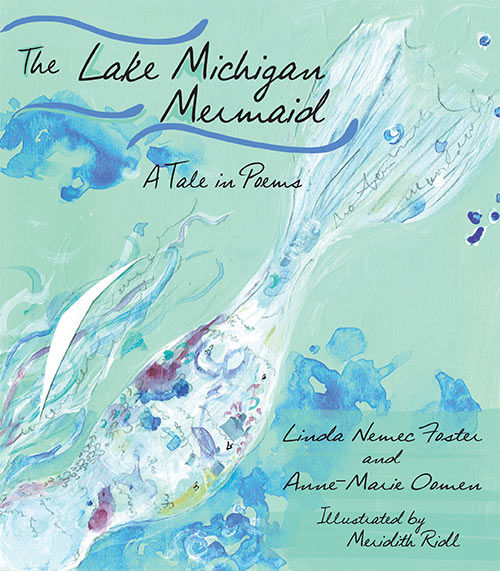

Based solely on its cover, The Lake Michigan Mermaid presents itself as a children’s book. It’s undeniably “pretty,” with an aquamarine background and flowy, romanticized script. And indeed, Foster verifies that this was their initial intention. “But,” she continues, “It soon became clear as the story line and depth of the poetry developed that we were speaking to a much broader base. As we look on it now, I think that it still fits in a young adult category, but it really is for young and old alike.” Oomen adds, “We were writing for a girl that is about the age of Lyk and the grownups involved. Someone who is thirteen, fourteen, with just enough of the life trauma and probably issues with a mom that they would identify with that.” But both insisted from the start that theirs would be no traditional, “Disney” mermaid, or even a “Disney” book, for that matter. Says Foster, “[The Mermaid] has depth and mystery that I think takes a slightly older imagination to appreciate, so I don’t think of our target audience to be young children; say, four or five years old.” They actually nixed their first three potential illustrators on that very basis: “[We were] looking for somebody who would understand that idea of the mermaid as a spirit rather than as a graphic. And almost everyone was too explicit—they were either deeply influenced by Disney, or they were giving away everything about the mermaid, giving her a face. We wanted the lake, the water, the currents to be her face.” In The Lake Michigan Mermaid, Oomen and Foster blend the two seamlessly. So seamlessly, in fact, we’re often left asking: where does human end and lake begin? But, as those of us who hear the call of the water know, this isn’t a question that’s just reserved for books. And it’s the mermaid herself — this imagined, but extraordinarily palpable water-spirit — that’s the vertex.

As the pair had originally pictured, there are two contrasting personalities that ultimately comprise the book’s storyline: Lyk, Oomen’s “seeking” adolescent, and Foster’s elegant, enigmatic water spirit, Phyliadellacia, which literally means “daughter of the sea.” And though each writer voiced only one set of poems, they both approached the idea of the mermaid and the accompanying lore from a deeply personal level. For Oomen, the connection is rooted in nostalgia—a love of the water that stems from the lake memories of her early childhood. But Foster’s association is far thicker than water: in fact, it’s more of a bloodline. Of Polish ancestry, Foster has a strong affiliation and familiarity with the iconic mermaid of the River Vistula, which directly intersects the city of Warsaw. As if their individual intrigue wasn’t reason enough, the two also discovered a long-standing tradition of Great Lakes mermaids among the area’s indigenous people. Lake Superior’s native tribes, in particular, maintain age-old stories of men and women dwelling below the lakes’ great depths. It was like the universe had sent them a message: the coastlines of Michigan desperately needed a mermaid, and Foster and Oomen were precisely the women to imagine her.

The actual writing process, however, was a far more time-consuming task than either writer could have anticipated. The two initially agreed to keep the process as low-key as possible from the very beginning: “one or two poems a month.” And then life happened: both women published multiple books and lost a family member in the interim. Their collective foci continuously shifted. It wasn’t until several years later in Northport, at another anthology reading, no less, that the two resolved to finish what they had started. Says Foster, “I suggested that we take several days, like a long weekend, in the near future and take a motel room somewhere and have our own workshop sessions. It was decided to find a place halfway between where we both lived that was on Lake Michigan to act as a catalyst for the mood that had begun to generate with the work up to that point. I found such a place in Manistee. We spent three days and completed it, coming to a conclusion and story line that neither of us had planned or considered.” Oomen adds, “That was when the sort of narrative, the real narrative came to the surface. That’s when we really said, it’s not just a call and response. That intense time together is when we really started to see the mermaid as the spirit of the lake, as the force of the water in us. That coalesced around that weekend.”

As it were, the process of actual writing took about eight years to complete, and then another two to bring the collection to publication. Following their initial pitch of the manuscript, the pair’s editor insisted that the poems be illustrated. Enter, Meredith Ridl: the completing member of this literary trifecta, and incidentally, the daughter of Jack Ridl, a lauded poet and the speaker who had posed the mermaid question in the first place. *Que The Twilight Zone theme music* Prior to discovering Ridl, the pair’s search for an illustrator had been nothing short of excruciating. They had already solicited three artists before considering Ridl, but both writers knew she was it the moment they saw her work. Says Foster, “[She] has really been able to take our work and give it a visual interpretation that we feel stimulates the imagination without limiting what each individual who reads the book brings to each page in their own mind, through his or her own eyes.” Oomen continues, “What we didn’t realize, is that when you have a really good illustrator, it’s not that they are drawing a picture of what the poem says: they’re actually adding meaning to the poems.” Ridl’s whimsical illustrations ultimately become the vehicle for Oomen and Foster’s verse. The book is positively brimming with shrouded symbolism that mirrors the accompanying poems: ciphered language in the waves, hints at Lyk’s blue shells tucked away in corners, and the ever-present whimsy of Ridl’s boundless watercolor. In short, “she understood,” as Oomen so succinctly puts it. Indeed, Ridl was the piece that neither Foster nor Oomen knew they were missing. And with their powers combined, the end result is nothing short of a masterpiece.

So, does this dynamic, hydrophilic duo actually believe in mermaids? In a word, yes; but, not how you might think. Both women have passionate faith in Phylliadellacia as the spirit of the lake, and both insist that they’ve felt her presence, even seen her. But both Oomen and Foster also see their mermaid as more of an enigma — a symbol, even — than an actual being. For Foster, she’s a poignant reminder that our Great Lakes, though boundless, are increasingly fragile and need protection: “What we have to do as human beings, specifically living in the Great Lakes region, is open ourselves to the fact that we are surrounded by one of the largest natural wonders in the world, which can feed our spirits as well as our bodies with its riches. We need to be good stewards of that resource. The Mermaid embodies that force of nature.” For Oomen, “The Mermaid is what the lake represents. The mermaid is bigger than just this creature in the water. In the end, she says, “I enter your dream.” That’s what water does to us: it enters our dreams. So, I’m hoping that if there is any larger critical reaction to this book, it would be that it begins to capture and communicate an awareness of water as a commons, and not a commodity. That’s what I really hope for it, but of course its first story is the story of a family; of a relationship and this larger idea of this spirit of water that permeates us all.” And permeate, she does. For the rest of us, The Lake Michigan Mermaid is a reminder that the lakes are a living, breathing entity; it’s the goosebumpy feeling that surrounds us in in their presence, even when we think we’re alone. But perhaps most importantly, it’s the validation that the Lake Michigan Mermaid really does exist, but only if we look closely enough to see her.

About the Authors:

About the Authors:

Linda Nemec Foster is both a poet and writer. She has authored eleven poetry collections to date, including the critically acclaimed Amber Necklace from Gdansk and Talking Diamonds. She is the founder of Aquinas College’s Contemporary Writers Series, and from 2003-2005, served as the first Poet Laureate of Grand Rapids. Foster’s work has been published in over 350 magazines and journals, and she has been honored with awards from The Arts Foundation of Michigan, ArtServe Michigan, The National Writers’ Voice, and The Academy of American Poets. In 2015, she received a Lifetime Achievement Award from the Dyer-Ives Foundation for her contributions in poetry and literary arts advocacy. Other notable books by Linda Nemec Foster include Living in the Fire Nest and Listen to the Landscape.

Anne-Marie Oomen is an instructor of Creative Writing at the Solstice MFA program at Pine Manor College in Massachusetts and a writer-in-residence for the Interlochen College of Creative Arts Writers’ Retreat. She is the author of the award-winning memoir Love, Sex, and 4-H, Michigan Notable Books Pulling Down the Barn and House of Fields. Oomen has also authored several plays, including the award-winning Northern Belles and 2012 CTAM contest winner, Secrets of Luuce Talk Tavern. Other notable books by Anne-Marie Oomen include An American Map: Essays and a full-length collection of poetry, Uncoded Woman. She is a founding editor of Dunes Review and the former president of Michigan Writers Inc. Oomen lives near Empire, Michigan, and makes regular appearances at writing conferences throughout the country.

Authors Next Door: Anne-Marie Oomen and Linda Nemec Foster