By Paul Oh

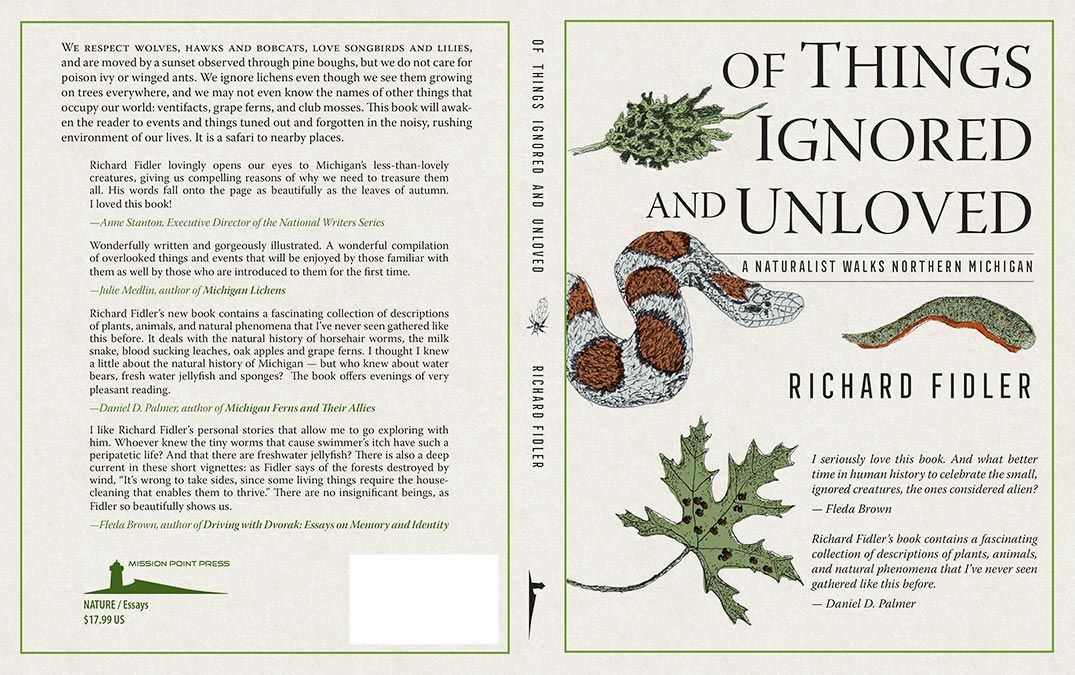

Beyond the obvious and bountiful beauty of northern Michigan, you’re likely to step on or over or under elements of nature you might think you’re better off without. Maybe that lamprey had latched onto and marred what would otherwise be an award-winning fish or that bad case of swimmer’s itch that arrived at your ankles by way of a lovely mallard. Underneath the layer of discomforting critters there are pieces of the natural world that we may never notice, from lichen crusted on trees in the woods to freshwater sponges. Traverse City author Richard Fidler investigates and explores these creatures and phenomena from a biologist’s perspective in his latest book, OF THINGS IGNORED AND UNLOVED: A NATURALIST WALKS NORTHERN MICHIGAN.

Could you tell me how writing figures into your life? Has writing been very present for your whole life or is this a more recent development?

Could you tell me how writing figures into your life? Has writing been very present for your whole life or is this a more recent development?

I taught biology for thirty-one years here in town at East Junior High and I didn’t do much writing at that time. On my retirement, which was a long time ago 14 or 15 years, I started writing. And I’d always been good at it. In high school I’d get compliments, you know. I went on and I got two bachelor’s, a master’s, and a doctorate. The doctorate being a doctorate in education. And of course you have to write to get that education. But in retirement, … I got interested in local history. And there was a niche to be filled. Nobody had written about local history with a view towards forgotten populations. Like, women, labor, dissidents, politics even: why do we almost always vote Republican up here? That’s a question that no one had really addressed, anyone who had written about history before. So I saw that niche. And I thought, I have something to say. And I ended up writing four books on history. And [Of Things Ignored and Unloved] goes back to my training in biology and it has to do with living things.

What sort of skills from being a teacher translated into writing, if any?

You know education’s all about communication. My classes were not boring. So, teaching it—it’s oral communication. And you know. If you cannot bore a 15-year-old, you’ve got it made because they have many other things more important than listening to me talk about biology. If I can get them to listen, I’ve already done it. I can write anything.

In terms of your writing process, how is writing about nature different than writing about history?

I think in both cases there has to be a story, something that grabs me. It starts with a question that needs answering; then you go to primary sources and try to find answers. Here’s a story that dealt with a question that there’s actually a bit of history: In the 1890s or 1880s out there in the bay they would report that the bay would suddenly start boiling and the water would shoot up and so on. I started asking questions. Did that occur after 1900? No, there’s no evidence that it did. And then well what could possibly have caused it? And then, you know, you go mucking around and making guesses and so on.

What in particular got you started on this most recent book?

I’m an editor for an online magazine called The Grand Traverse Journal published through the Traverse Area District Library. It’s mostly about history, but I write about nature once a month. But I needed an organizing theme for the book. And then it just occurred to me that everything that’s here is either something people don’t know about, like freshwater sponges, or things that they don’t like, like snakes or leeches. So that was the organizing theme.

So what kind of challenges have you faced in writing nonfiction?

There’s always the fear a writer has that he’s boring his audience. That’s my greatest fear. What can you do to make something come alive? One thing I could do, I can draw. So I did the illustrations here. There’s also a way to write history. It’s not fiction, really. When I’m describing what the weather was like that day, I went to the weather reports. I know what the weather was like. But you know that’s the thing, you can write history and it sounds like it’s fiction or it looks like fiction, but it’s not. You can document everything—it’s there.

You mentioned story as a starting place. What sort of stories really jump out at you as wanting to be written?

One was—and this ties in with your question and my own personal experience—about how across the street from Horizon bookstore there was a horrendous fire 1898. It took out twelve wooden buildings on one side and it jumped over the street and took out some wooden buildings here, including the wooden building that existed [where Horizon stands today].

I read about that in an old newspaper. Across the street from [Horizon], they were just starting the new building that’s there now. They had a hole dug in the ground. So this question came up: Is there any evidence of the 1890 fire that still exists? So when the hole was dug in the ground, I went over there and went under the yellow tape. And I started looking.

Back there was a layer of charcoal. And then I dug out the old square nails that they used for construction. And then there was crockery that I found. Broken crockery. One of which had the tea maker’s name with which I could go online and Google, and sure enough they were making pottery back then. It was all there. Now that’s a story that’s kind of interesting.

That story I was able to write a little bit in the manner of Doug Stanton where you had the firemen talking outside of the firehouse. What the weather was like. The glow that they could see. In the sky. They knew there was fire. They would have seen a glow. You can’t miss it. And then newspaper accounts telling how it all came together to put the fire out here. If it’s history I go to the old newspapers and find something that just jumps out at you.

What do you think it is about your stories that makes them so engaging.

That was interesting because I asked a question, “Can the remains of the fire still exist over there?” and then I got the answer. So I guess with me sometimes it relates to my personal experience. You know that’s what makes it interesting to me and I guess that makes it interesting to others.

Is there anything that you’d like to say about writing that I haven’t really asked about?

All I can say is edit, edit, edit. First, you need a clear idea about what you want to say. Some people can just sit down and it flows. For me, there’s some of that but I write down at least single words about things that I definitely want to talk about. Then, at that point, it may be necessary with this kind of writing to do research. And that can take quite a while. Once you do the research, then you have a clear idea what you’re going to say and you say it, then you edit it.

But the best editor to begin with is you, yourself. And the way you edit is to read your work aloud. Read it aloud and as you do that, you’ll stop and say “It’s not flowing”, “They’re not going to understand this” or “How does this fit with that?” After that, you need to take it to somebody else to edit or read aloud to or whatever. And then I guess you’re done already. But you know what? With beginning writers, there’s too much of a tendency to say “Well it’s done” and then put it on a shelf.

I don’t see the point of writing if you don’t share it with people. And how many of these have I sold? Five hundred that’s what I’m guessing. OK. But I shared it with some people. Of Things Ignored and Unloved just came out. It’ll probably sell five hundred copies, too. But I don’t think any writers should aim to be successful, necessarily. I think a writer should just aim to be read by some people. Maybe only those in your family.

Thank you for sharing your insights.

Just remember, good writing is always a back and forth. It’s never just one side.

Editor’s note:

Paul Oh is a student of Front Street Writers, an intensive writing workshop taught at the Career Tech Center in partnership with the National Writers Series. He is a senior and will attend Colorado College.